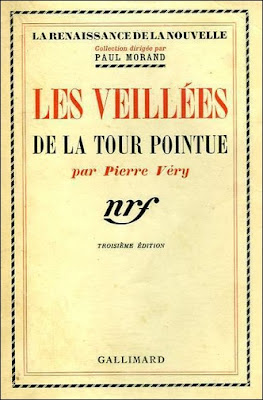

I mentioned in my review of the third Joseph Spector novel, Cabaret Macabre (2024), Tom Mead has been a busy bee with not only working on the fourth title in the series, The House at Devil's Neck (2025), but branching out in translating French detective short stories and novels – starting with Pierre Véry's Les veillées de la Tour Pointue (The Secret of the Pointed Tower, 1937). Mead has been commissioned by Bedford Square Publishers to translate Paul Halter's impossible crime novels. Fingers crossed for a translation of Le voyageur du passé (The Traveler from the Past, 2012). But wait... there's more!

Last November, Crippen & Landru published a short story collection with a selection of Mead's own work. The Indian Rope Trick and Other Violent Entertainments (2024), introduced by Martin Edwards, containing eleven short stories. Three of which appearing in print for the first time. I thought it would make for a perfect follow up to the previous review of John Dickson Carr's collection of short stories The Men Who Explained Miracles (1963). So let's dig in!

"The Indian Rope Trick," originally published in the July/August, 2020, issue of Ellery Queen's Mystery Magazine, finds Joseph Spector refereeing a challenge between two magicians, Ferdinand le Sueur and Doctor Gupta, who have been arguing about the Indian Rope Trick – former claims to have come up with "a perfect mechanism for working the trick." Something entirely new and revolutionary. Doctor Gupta performs the trick under traditional circumstances, inside a theater, but Le Sueur demonstrates his version of the trick under an open sky! Even more, he pulls off the trick and that alone should earn the story a spot in a future locked room anthology. But murder interrupts the challenge when one of the magicians is strangled without leaving behind a single footprint on the muddy driveway. Spector is the impartial witness to the cast-iron alibi of both suspects.

The solution to the impossible murder is not bad. Just a bit skeptical about one part of the trick, because I don't think doing that, so casually, is as easy as the story suggests. Even with that to help. Still a pretty good impossible crime story, overall, succeeding where John Basye Price's abysmal "Death and the Rope Trick" (1954) failed all those decades ago.

I can only imagine "The Octagonal Room," originally published in the anthology Millhaven Tales (2018), came about after Mead read the shin honkaku mysteries by Soji Shimada, Yukito Ayatsuji, Takemaru Abiko and saying, "I'll give it the old college try." Spector is drawn to the home of Simon Eldridge, an American writer, who moved to England and took residence of a reputedly haunted house, Black Mill. Beside stories of robed figures, satanic rites and "bonfires blazing in unoccupied rooms," Black Mill has an architectural mystery. The place has a strange, octagonal room not any of the original architectural plans and sketches, but nobody knows who or when it was added to the house. Some malevolent, otherworldly force or eldritch horror appears to reside in the octagonal room and has taken possession of Eldridge. Spector is not the only one who came to Black Mill to investigate, but the magician-detective eventually has to solve another impossible crime when Eldridge's decapitated body is found lying inside a pentagram in the locked octagonal room.

I figured out for the most part how the trick was pulled off and who was behind it, but nothing to the detriment of this fantastic and original locked room mystery, nor my immense enjoyment. "The Octagonal Room" is the best short story in this collection and now my favorite Mead locked room mystery.

"Incident at Widow's Perch," originally published in the September/October, 2019, issue of Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine, has a great backdrop for a detective story with impossible crime to match taking place at a house built into peak – known as Widow's Perch. A desolate summit so remote "it was accessible only by cable car." Giles Latimer's body was found by his wife, Margot, sprawled on the rocks at the foot of the cliff. The police wrote it off as an unfortunate accident, but Margot has good reasons to believe he was murdered and now murderer is out to get her. So she turns to the magician-detective, Joseph Spector, who quickly loses his client under seemingly impossible circumstances. Spector is one of the people who sees Margot enter the cable car alone, pulled the glass door shut and began its descent downwards from the peak, but mid-way through, Margot burst into flames. So another rock solid impossible crime story, curiously more reminiscent of Arthur Porges than Clayton Rawson.

"The Sleeper in Coldwreath," originally published in the March/April, 2023, issue of EQMM, wonderfully plays on that old, hoary trope from the pulps. Hypnosis! Something that makes most of us shudder whenever it turns up in a proper detective story or locked room mystery, but Mead found a good use for it in this short story.

Forty years earlier, in 1893, the house known as Coldwreath was the property of a psychic researcher, Dr. Peberby, who specialized in "sleep, dreams and hypnosis" ("a cocktail of mysticism and blasphemy"). One day, Peberby locked horns with a skeptic, Lester Brownlow, who challenged him to demonstrate and prove his hypnotic powers. What happened next has haunted Coldwreath ever since. Peberby invited Brownlow to Coldwreath to be placed in a hypnotic trance, while witnesses were present, before being guided to an upstairs bedroom – commands him to lock and bolt the door behind him. Thirty minutes later, the house is rocked by an unearthly scream and three men had to break down the bedroom door, but the room was empty without a trace of Brownlow. Ever since, the place has been haunted by an apparition with half-lidded eyes as though in a trance ("a phantom sleepwalker, wandering between the worlds"). Spector comes to investigate and naturally is present when somebody else impossibly vanishes from a locked room and a body turns up under equally impossible circumstances of the no-footprints variety. This story would have made for a great Jonathan Creek episode and enjoyed the solution to the disappearance from the locked bedroom. A trick based on a locked room idea, or concept, that always amuses me (ROT13: qbbef gung nccrne gb or ybpxrq, obygrq naq frnyrq).

"The Footless Phantom," originally published in the March/April, 2022, issue of EQMM, brings Spector to the dying mining village of Greeley in the Cotswolds of western England. A village that had been dealt a fatal wound when a mining accident killed numerous miners and workers moved to others mines in the region, which left behind a dwindling population who stuck around. So the village has problem of its own and more problem is added to the list when the troublesome Danny Snape is found dead with the back of his head caved in at the foot of a cliff. There's only a single track of footprints going from Snape's van to his body and if the weapon was dropped from the top of the cliff, then what happened to it? So it appears the murder could have only been committed by "a weightless, invisible assassin."

Not a bad premise for an impossible crime story, nor is the backdrop of a dying mining village, but plot-wise, it felt ropy – especially how the whole impossibility was rigged up. So not the best impossible crime story to be found in this collection.

"What Happened to Mathwig," first published in the anthology Wrong Turn (2018), is Mead's take on Herbert Brean's The Traces of Brillhart (1961). A Harley Street psychiatrist begins a relationship with one of his patients, Claire Mathwig, who ends up agreeing to kill her husband, Chester Mathwig. And how! Chester Mathwig ends up with three bullets ("...final bullet hit him in the skull...") before disappearing into the waters of the Thames. So imagine the murderer's shock when his victim turns up, alive and well, with nary a scratch or flesh wound. Enough to run to Spector to confess and ask him to explain how Mathwig pulled a Rasputin. The solution is as grim as that historical, hard-to-kill figure. One of the better and stronger plotted stories in the collection with a tantalizing premise that has barely been scratched by impossible crime and locked room specialists, past and present.

The next non-series short story, "Invisible Death" (2018), but already reviewed it a few years ago together with Mead's "The Walnut Creek Vampire" (2020).

"The Three-Minute Miracle," first of the three previously unpublished short stories, which combines the problem of the unbreakable alibi with the head scratching phenomena of bi-location. Spector is consulted by his old friend, Inspector George Flint, who's investigating the murder of a rich philanthropist, Mrs. Anthea Wheeldon. She was shot and killed by her no good, criminally charged nephew, Alec Mellors, whose little blackmailing enterprise is possibly going to land him in prison. And his aunt is determined to cut him out the will. Alec not only has a motive, but he was seen entering the house and pulling the trigger by an impartial witness. There is, however, another equally credible witness swearing he was fifty miles away, three minutes before he was seen firing the fatal shots!

I'm in two minds whether, or not, the story qualifies as an impossible crime. I think most of you are aware of my hesitation to qualify unbreakable alibis as impossible crime, unless the alibi hinges on the murderer appearing to have been physically incapable of having carried out the crime. Not when the alibi turns on witnesses or paperwork. On the other hand, the murder committed in front of a witness in combination with the alibi gives it the appearance of bi-location. Either way, Spector finds a way to break his cast-iron alibi down with the only smudge on his ingenious solution is that one, not unimportant, detail is impossible to anticipate. Other than than, "The Three-Minute Miracle" will please fans of Christopher Bush and Tetsuya Ayukawa.

"The Problem of the Velvet Mask," second previously unpublished short story, takes place during Christmas, 1931, which begins when Juliette Lapine comes to Joseph Spector on behalf of her father, Lucien Lapine – a retired French diplomat. She believes her father is in danger from their new next door neighbor, Eustace Dauger, who arrived in a funeral car ("like the grim reaper himself") and always wears a velvet black mask. Lucien Lapine reacted to his arrival "as though he had been expecting him for many years." Eustace Dauger possibly is Felix Duchesne. One of the two main players in the "the Duchesne Affair," an espionage case from some twenty-five years ago, whose downfall came at the hands of Lapine. Felix Duchesne, "accused spy," reportedly died as a prisoner on Devil's Island. Or did he?

Lucien Lapine is shot and killed in "an impenetrable room" with the windows locked from the inside, the door locked with the key inside the lock and the two detectives were standing outside the door. Not the mention that the snow outside is unmarked. Interestingly, there's a good amount of "the blinkin' cussedness of things in general" going on, but not used to create the locked room murder. A route Carr would have taken. Here it takes place all around the locked room murder, which has a somewhat prosaic solution, but also a good example a touch of cleverness and ingenuity can be applied to a simple idea. I was entertained!

"Lethal Symmetry," third and last of the previously unpublished stories, is one of the shortest works in the collection and an unexpected gem. Inspector Flint calls upon Spector to help him out with the strange murder of Conrad Darnoe. A man who "prized symmetry above all things" and got himself impossibly poisoned in a locked room. The brilliant solution is a clever and even original variation on a impossible poisoning situation/trick I've seen only once before. No idea if Mead has read that particularly story, but this is a good, new way to use that trick.

There's one last story, "Jack Magg's Jaw" (2022), but reviewed it last year as part of "Locked and Loaded, Part 4." The Indian Rope Trick and Other Violent Entertainments ended on a high note for me with the strong, short and excellent "Lethal Symmetry."

Strong, short and (mostly) excellent perfectly sums up The Indian Rope Trick and Other Violent Entertainments. A collection of a short impossible crime stories representing another fresh and promising page in the budding locked room revival and should entertain fans of the Joseph Spector novels until The House at Devil's Neck is released.

Speaking of the locked room revival, I've accumulated a small pile of modern impossible crime novels over the past two months and holidays. So I'll begin decimating it presently, but first, back to the Golden Age!